Collection Gems: August 2017

With the Centennial of America’s entry into “The Great War”, the recently concluded sesquicentennial of the American Civil War, and the bicentennial of the War of 1812 one could be forgiven for overlooking the fact that we were at war with Spain almost 125 years ago.

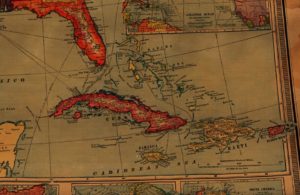

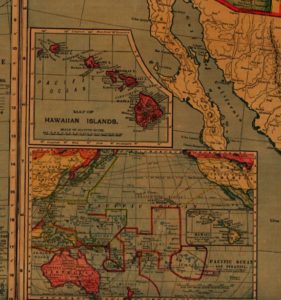

Map number 95 in the Society’s Map Collection is dated 1900 and is entitled “The United States and its new Possessions” (Figure 1; the full map is too large for a scan), representing the new age of the American Empire. The “new Possessions” illustrated on the map are a direct result of the Spanish-American War (with the exception of the Alaska Territory, obtained by “Seward’s Folly” when the land was purchased from Russia in 1867 for $7.2 million).

On 23 April 1898, Spain declared war on the United States, which had commenced a blockade of Spanish-ruled Cuba two days earlier. The US “returned the compliment” on 25 April, formally declaring war on Spain. The reasons resulting in armed conflict included the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, American support for uprisings in both Cuba and Puerto Rico, and the “yellow journalism” (read: William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer) blaming Spain for these issues. The “splendid little war” (a phrase coined by then-Secretary of State John Hay) was the first significant overseas military action in which the United States was involved.

The War quickly morphed into a battle for Empire when American forces steamed to the Philippines rather than initiating fighting in Cuba. Only 11 days after war was declared, the Spanish fleet was dealt a major defeat at Manila Bay by the American fleet under Commodore George Dewey. The loss of its naval force compromised the Spanish defense and rendered a land conflict in The Philippines more or less unnecessary. American priorities changed, resulting in an invasion of Cuba on 10 June 1898. This began with a successful invasion at Guantanamo Bay, followed by land victories at Las Guasimas, El Caney, and San Juan Hill, where the Rough Riders – led by Theodore Roosevelt – successfully assaulted the Spanish positions on adjacent Kettle Hill, thereby encircling the Spanish defenses. The Spanish fleet steamed away from this encirclement and lost all its ships in the ensuing battle of Santiago on 3 July, resulted in the surrender of Cuba. The successful invasion of Puerto Rico followed on 25 July. Without a fleet, Spain could not successfully defend the island and surrendered the island.

The lopsided nature of the fighting convinced Spain to agree to the peace terms offered by President William McKinley on 9 August, with a truce (the Peace Protocol) signed three days later. Negotiations dealing with territorial issues resulted in Spain ceding the Philippine Islands (Figure 2), Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States in exchange for $20 million, and granting Cuba independence (Figure 3). The War officially ended 10 December 1898 when the Treaty of Paris was signed.

The War’s legacy lives on. Even today you read about Guantanamo Bay, Puerto Rico, and the large US military presence in The Philippines. We also gained the first US possession in the Pacific – Guam – and the War served as a pretext to take control of Hawaii when the Government, citing the strategic use of the existing naval base at Pearl Harbor, approved formal annexation. Two years later, Hawaii was organized into a formal U.S. territory (Figure 4). As a result of the Spanish-American War, the American Pacific Fleet was stationed at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.