When Durham Boats Were a Sweet Ride

By Rick Epstein

Durham boats had their moment in 1776 when they carried George Washington and the Continental Army across the Delaware to win the Battle of Trenton.

But did you ever wonder what those boats were doing when they weren’t getting their picture painted by Emanuel Leutze?

According to tradition, the first Durham boat was made circa 1730 by Robert Durham near the Durham caves just south of Riegelsville, Pa.. It carried iron smelted at the furnace in Durham, Pa., to market. These boats became the primary cargo vessel on the Upper Delaware.

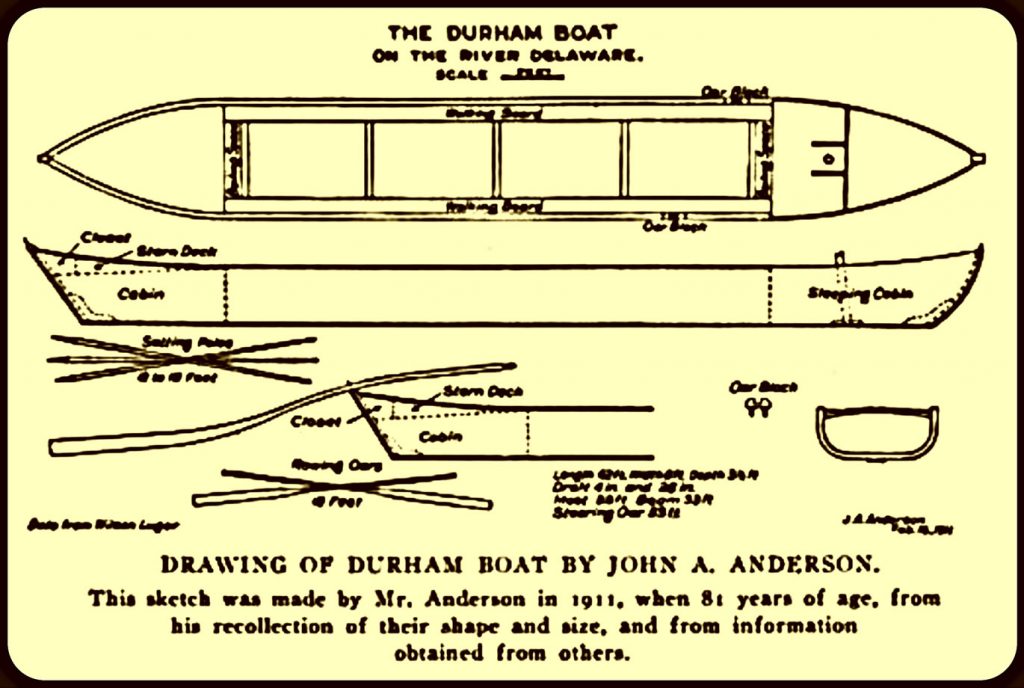

Mansfield Merriman of the U.S. Corps of Engineers, writing in 1873 after the boats were no longer in use, describes them as “round-bottomed boats pointed at both stern and bow, about 60 feet long, 10 wide and 5 deep, with a low cabin for sleeping apartment, and one aft for provisions; the center of the boat was left free for the load.”

Goods carried down the Delaware might include flour, corn, corn meal and casks of pork – 150 barrels of flour at a time, or 15 to 16 tons, according the Hunterdon Independent in 1877.

“When fully loaded,” wrote Merriman, “they drew about 30 inches; the usual load on the down trip being 20 tons, on the trip up five to ten tons. The time required for a trip from Easton to Trenton was one day, while the return trip normally occupied three days.”

John A. Anderson (1829-1917) wrote, “On the Delaware, the crew usually consisted of three men,” floating downstream with the current, aided by a pair of 18-foot oars. “Moving up stream the boat was usually propelled by ‘setting poles,’ 12 to 18 feet long and shod with iron. On the thwarts was laid, one each side, a plank 12 inches wide. On these ‘walking boards’ members of the crew, starting at the forward end, with poles on the river bottom and top ends to shoulders, walked to the stern, pushing the boat forward. While they rapidly returned to repeat the process, the captain, who steered, used a pole to hold the boat from going back with the current.

John A. Anderson (1829-1917) wrote, “On the Delaware, the crew usually consisted of three men,” floating downstream with the current, aided by a pair of 18-foot oars. “Moving up stream the boat was usually propelled by ‘setting poles,’ 12 to 18 feet long and shod with iron. On the thwarts was laid, one each side, a plank 12 inches wide. On these ‘walking boards’ members of the crew, starting at the forward end, with poles on the river bottom and top ends to shoulders, walked to the stern, pushing the boat forward. While they rapidly returned to repeat the process, the captain, who steered, used a pole to hold the boat from going back with the current.

“Sometimes the nature of the banks admitted of drawing the boat along by catching hold of the overhanging bushes, a process known as ‘pulling brush.’

“The boat as a rule was painted black and was without a special name. A moveable mast, 6 inches in diameter, and 33 feet long, with a boom of the same length and a three-cornered sail, enabled the boat to sail upstream when wind favored.”

Anderson, who lived in Lambertville, was superintendent of the Belvidere & Delaware Railroad in 1870-1886, and the Delaware & Raritan Canal, 1886-1900. Author of “Navigation of the Upper Delaware,” his Durham-boat expert was 78-year-old Wilson Lugar (1832-1900) of Solebury Township, Pa., a retired carpenter.

Lugar had owned and operated a Durham boat. In 1862 that he took a cargo of ship’s knees (curved wooden braces) across New Jersey via the Delaware & Raritan Canal to New Brunswick, where the boat was towed down the Raritan River and into the Brooklyn Navy Yard to deliver the cargo to Uncle Sam. The boat, alien to New York Harbor, caused a sensation. Naval officials asked how he got there from the Delaware, Lugar quipped, “I came across the country on the dew.” Vessels entering the Navy Yard had to be registered by name, so Lugar borrowed one from the Navy itself – The Monitor. He was kept busy answering questions to satisfy the curiosity of the intrigued workforce.

Lugar also told Anderson that his boat was the last one working on the river and it made the final Durham-boat voyage down to Philadelphia, delivering a load of shuttle blocks (textile equipment), in 1865.

Lugar rhapsodized to Anderson, “The Durham boat was the most beautiful modeled boat I ever saw. Her lines were perfect and beautiful. Her movement through the water was so easy, with such a clean run aft, that she left the water almost as calm as she found it… They could outsail any boat I ever saw sail, with a fair wind. Of course they could not work to windward, as they were too long and had no centre board. We could sail up any falls on the river.”

Anderson wrote, “It is said that at one time there were several hundreds of these boats on the river. The largest fleet was at Easton, from which place were shipped large quantities of grain, whiskey and other products. At Coryell’s Ferry and Wells’ Ferry, now Lambertville and New Hope, a large number of boats were owned, these points being centres for a considerable population producing materials for transportation to Philadelphia. Many were owned at other points on the river.” Some of the boats traveled in fleets, which enabled their crews to “double up” and help each other through difficult places, like the rapids south of Lambertville.

The opening of the first section of the Delaware Canal in 1831 was the beginning of the end for the Durham boats. The Durham boats could use the canal, and some did use it to go upstream, but they were charged double for a one-way passage. But a canal boat could carry much more freight – 80 tons of upstream or down.

The Flood of 1841 swept away many of the old Durham boats, but Lugar’s vessel lingered in a wide part of the canal until the Flood of ’03 took it, Anderson reported.